Ben Barnhart Photo

Amherst’s Yiddish Book Center recently underwent a major renovation.

It is one of the most important Yiddish institutes in the world. The Center’s website offers an array of resources that are essential for both Yiddish researchers and enthusiasts. But since its founding in 1980, the Center’s vast collection of books and other materials has mainly lived in underground vaults and off-site storage facilities — largely inaccessible except to researchers visiting by appointment.

Now, all of this has changed. The Center’s new permanent, public exhibition, “Yiddish: A Global Culture,” features hundreds of books, photographs, works of art, memorabilia and other objects displayed in a large and beautifully organized exhibit space. The Yiddish Book Center is now a museum and showcase for Yiddish cultural material.

“We wanted to make Yiddish culture cool. Seriously cool,” said David Mazower, the chief curator and writer for the exhibition. The stereotypes of Yiddish being dead, dying, or irrelevant had to go. The vitality and daring of Yiddish literature, art, music, journalism and theater — which burst onto the international scene in the late 19th century, and never paused to breathe until the catastrophe of the Holocaust — needed to be shown to Jews themselves and to the world in its true and brilliant colors.

Shakespeare’s sonnets in Yiddish

In the center of the complex, the exhibit is in the main building. The Yiddish Book Center is a collection of low wood structures, with steeply shingled roofing that evokes an Eastern European shtetl. The visitors look down from a balustrade onto an area once filled with metal bookcases. To make room for the exhibit, 30,000 books were boxed and moved. The 60-foot long mural, created by German artist Martin Haake for this exhibit, depicts the history of Yiddish Culture.

The ramp is lined with books from the Center’s collection that give a sense of the huge range of topics that appealed to Yiddish writers and readers: Shakespeare’s sonnets translated into Yiddish (1944); Avrom Sutzkever’s chronicle of the Vilna Ghetto (1946); a Yiddish introduction to Islam (1907); the children’s fantasy-adventure novel, Yingele Ringele (1929); Charles Darwin’s Origin of Species The first Yiddish book was published in Vilna in 1920. Other notable books include Japanese folktales in Yiddish and a History of the Republic of China, which were among the final Yiddish publications in Vilna just before the Holocaust. There’s also a much more recent endeavor: Herman Melville’s Moby DickTranslation into Yiddish is scheduled for 2021.

The exhibition area is festooned with two rows of colorful double-sided banners — each reproducing a Yiddish book or magazine cover — under the central skylight. A space this size could easily become overwhelming, but Mazower subdivided it into 16 thematic sections including bestsellers, Soviet Yiddish, women’s voices, press & politics and theater. Each section has a unique layout, shape and combination of objects and text. There are no barriers between the sections: Each feeds naturally and fluidly into others, suggesting the interconnectedness of all aspects of the Yiddish story — and of the Yiddish diaspora itself in time and space.

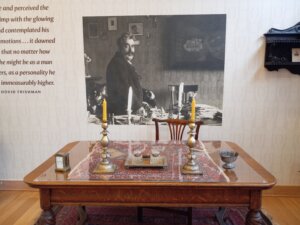

Replica of I. L. Peretz’s “salon” in Warsaw

Across from the bottom of the entry ramp — self-contained but inviting and accessible — is a section called “Peretz’s Salon.” It recreates the study in the Warsaw apartment of Y.L. Peretz was one of the founders of Yiddish modern literature at the end of the 19th century. Peretz’s study is where he gave advice to young Yiddish-speaking writers who later went on to become famous. On the wall behind the photo of Peretz, a replica of his desk stands in front. Books by writers in Peretz’s literary circle line the walls, and sound recordings of readings from those books float in the air.

Among the many impressive pieces in the exhibit is an extraordinary over-life-size “micrograph” portrait of the Yiddish writer and thinker, Chaim Zhitlowsky — consisting of thousands of hand-inked Yiddish words from Zhitlowsky’s texts. Guedale Tenenbaum was a Polish-Jewish textile worker who lived in Buenos Aires during the 1940s. He created it as a memorial to a person he admired. Tenenbaum made portraits in micrograph form of Jewish writers like Y. L. Peretz and Sholem aleichem, as well as H. Leivick. The Center purchased the Zhitlowsky Micrograph in 2018. It was covered with mold, water stains and had been torn into two. It was thrown away in the garbage when the former owner of the micrograph closed. After expert conservation, it’s a marvel.

The book I found beautiful was from 1921. Himlen in Opgrunt (“Heavens in the Abyss,” a poem by Chaim Krol). Esther Carp was the Polish-Jewish modernist artist and printmaker who created both text and illustrations. Her work is now being appreciated. The book — one of a handful of surviving copies — was open to an illustration whose vivid, saturated colors and bold composition absolutely leapt off the page. Amazingly, this magnificent volume was hiding in the Center’s own vaults, among a group of unprocessed donations.

Translations into Yiddish of Black American Literature

One section of the exhibit featured books and photographs that showed how Yiddish writers and readers grappled with race and racism in the United States, including Yiddish translations of Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin and Langston Hughes’ The Song of Black Folk. The most remarkable song was the Yiddish poem by Dora Teitelboim, about 1957’s desegregation at Little Rock Central High School (Arkansas), illustrated by Black artist and activist Ollie Harrington.

It was interesting to see a large collection of old Yiddish-language typewriters. Some were owned by famous female writers, such as Blume Lempel or Chava Rosenfarb. The clacking fingers of these women were easy to imagine. They wrote all sorts of Yiddish text on the keyboard.

Original posters, photographs and letters brought the glamourous world of Yiddish Theaters to life. A striking oil portrait by Yiddish film and stage star Ludwig Satz of Second Avenue Yiddish theatre legend Celia Adler was displayed.

The steamer trunk of Peretz Hirschbein, a famous Yiddish couple of writers, and Esther Shumiatcher from the 1920s gave an idea of how interconnected Yiddish cultures are around the world. They took this trunk around the world to visit other Yiddish figures, and see the sites.

A copy of Hersh Fenster’s Undzere Farpaynikte Kinstler (Our Martyred Artists), written in 1951 to commemorate Jewish artists in Paris murdered by the Nazis, gave a stark sense of what Yiddish-speaking artists achieved in the first part of the 20th century — and of the creative talents decimated by the Holocaust.

The Forverts Linotype Press from 1918

It was an incredible black and intricate 1918 Linotype Press that belonged to the Forverts Newspaper. The press is 7 feet high and weighs 4500 pounds. It was fascinating to study its gears, springs, and levers. I also studied the dirty and worn Yiddish keyboards that were used to input the text for the printer. The thought that I would be writing articles for the exact same magazine, using such a different type of technology was both strange and moving.

I was also fascinated by displays on children’s books, as well as women’s bibles in Yiddish (since religious women in Europe were usually not taught to read Hebrew); 500 years of Yiddish poetry written by women; the Kultur-Lige — a socialist Jewish organization established in Kiev in 1918, that promoted Yiddish language, literature and theater; the Yiddish radio research done by Henry Sapoznik; popular “shund” (trash) literature, including stories about detective Jewish Max Shpitskopf, the “Viennese Sherlock Holmes.” (Isaac Bashevis Singer devoured Shpitskopf stories as a boy.) A wooden box containing a card-index of Yiddish titles was also notable in Samuel Judin’s personal library. You’ll also find the original puppets used in Yiddish puppet theater by Zuni Maud and Yosl Cutler.

All the explanatory texts at “Yiddish: A Global Culture” are in English, so no knowledge of Yiddish is required to visit. For me, wandering through the exhibits was an act of homage: Here in front of me, accessible yet fragile, were treasures of the Yiddish culture I’ve come to care about so deeply. I’ve rarely felt more intimately connected to Yiddishkeit in all its wonder and variety.